Winning designs: what section 80e appeals reveal about achieving a successful design

Life as a planner sometimes feels like a hobbit trying to steal gold from under the dragon. Brave applicants may successfully use NPPF paragraph 80e to seize the prize of planning approval from a ferocious LPA. Every year isolated homes get planning permission on the basis of exceptional design. What nuggets of gold do their stories hold, and what can we learn from them to sharpen our skills?

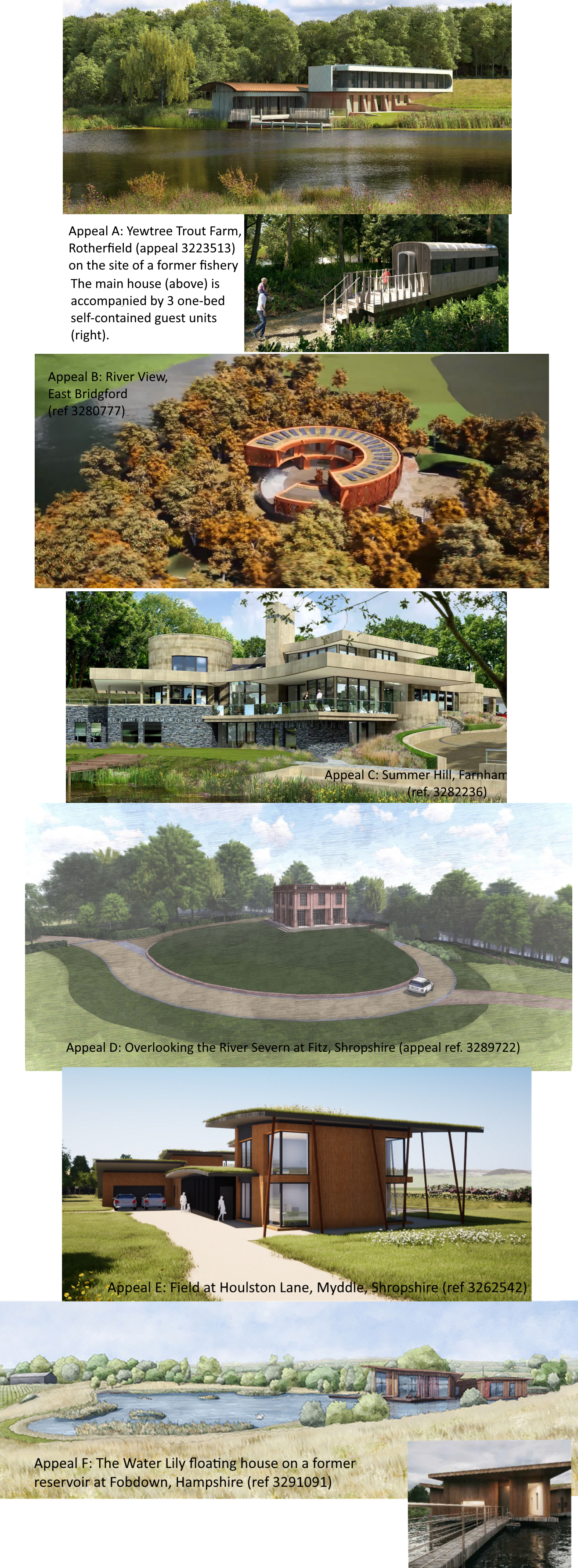

In six inspiring planning appeal examples we examine three appeals allowed and three dismissed, highlighting what works and what does not. First, it’s worth noting how national policy has shifted over time.

Changes to NPPF 80(e) policy that lowered the bar

Exceptional designs have been allowed to outweigh normal planning constraints since the ‘country house’ clause in PPG7 in 1997. Initially success was famously described by Hawkes Architecture as rare as, “Golden-egg flying unicorns”. However each iteration of the NPPF has been steadily lowering the bar. A simplification to the wording appeared in 2012 NPPF paragraph 55, then key words were removed in the 2018 NPPF paragraph 79 and 2021 NPPF paragraph 80e. As a result it is no longer necessary for proposals to be “innovative” or “groundbreaking” or “contemporary”. The policy is no longer to be used only “very occasionally” or in “special circumstances”. Today's NPPF 80e can now be applied to relatively modest houses, making it relevant to far more schemes.

The flamboyant artist Salvador Dali reputedly said, "Have no fear of perfection -- you’ll never reach it." It’s comforting to note policy 80(e) does not require perfection.

Current NPPF definition of exceptional design quality

The 2021 NPPF paragraph 80e contains 4 tests, all of which have to be met. It states:

80. Planning policies and decisions should avoid the development of isolated homes in the countryside unless one or more of the following circumstances apply:

….e) the design is of exceptional quality, in that it:

- is truly outstanding, reflecting the highest standards in architecture, and would help to raise standards of design more generally in rural areas; and

- would significantly enhance its immediate setting, and be sensitive to the defining characteristics of the local area.

The purpose of this article is to explore the wider lessons from such cases, including designs in more urban areas, but for those seeking to rely on paragraph 80e please note its direct application is of course limited to “isolated homes in the countryside”. This is defined in Braintree DC v Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government 2018 WL 01513032 and City & Country Bramshill Ltd v Secretary of State for Housing, Communities And Local Government & Ors [2021] EWCA Civ 320, which confirmed that the question to grapple with is whether a development is physically isolated from a settlement, rather than isolated from other buildings. If the site is not “isolated”, policy 80(e) does not apply.

Back now to those design nuggets of gold that can enliven the day job when working on more typical residential developments.

Six exemplary designs at appeal

Six policy 80(e) appeals are sketched below. Three were allowed and three dismissed, with as many valuable insights in those who lost as in those who won. Readers may wish to cast their bets now as to which of the designs were ultimately successful – all shall be revealed shortly.

The right site is key to success

The three successful appeals all involved sites offering opportunities to “significantly enhance its immediate setting”, making this the number-one attribute for success. Commiserations to our architects.

Successful appeals A and F were both sited on former reservoirs that were considered to be man-made environments. As previously developed land (brownfield waterbodies) it was easier to make a case that the proposals improve the existing site.

A ‘natural’ site, even if weed-infested, proves a much more difficult proposition. Unsuccessful appeals B, C and E were dismissed despite all having well thought-through designs. A common reaction is typified by the Inspector in unsuccessful appeal C (ref 3282236), who mused, “the appeal site where the new dwelling is to be located is perceived as an area of natural vegetation and tree cover, which is attractive in its own right. Whilst the proposed new dwelling might also be considered attractive as a result of its architecture and setting, it represents a change as opposed to a quantifiable improvement, and I do not find the argument that it represents a major beneficial effect a convincing one. The effect of the proposal would be to exchange one set of attractive views for a different set and, thus, would be a broadly neutral effect rather than a significant enhancement.” Hard luck to those who wish to replace natural environments with human artforms.

Greenfield sites are all too easily given fatal body blows, but our third successful appeal D (ref. 3289722) overlooking the River Severn proves there is still hope. At first glance it seems unlikely that a convincing case could be made for a site on agricultural land to, “significantly enhance its immediate setting.” Nevertheless, the appellants presented the future management of existing woodland and grassland around the property as a long term benefit. Securing good management of its surroundings enabled the Inspector to be, “satisfied that the development would have a significantly positive visual and operational relationship with the surrounding land.”

It may seem a bit of a cheat, but time-travel to bring the future of the setting into the equation may be just enough to persuade a planning Inspector. It certainly worked in this case.

Integrating a development into the landscape

Blending a development into the landscape is very difficult to achieve successfully. A green roof and lines that echo the landscape failed to convince the Inspector in Appeal E (ref. 3262542) at Myddle who decided, “the curved roof would provide little contribution to softening the form of the building in the rural landscape since the building would still largely project two storeys above ground level. As such, the proposal would significantly harm the rural character and appearance of the area.” You could be forgiven for wondering whether a building has to be invisible to be acceptable.

In appeal C the Inspector was impressed by the design but admitted, “Integrating a contemporary, modernist, design of dwelling into a very rural landscape is a challenging design exercise as the contrast between the built form and the landscape is very high.”

If it is difficult to be a shrinking violet, is being a sunflower a more successful strategy? Or a water lily, in the case of appeal F. Certainly all three successful appeals A, D and F refuse to hide in the landscape. Appeal D sits proudly on a greenfield site and was acknowledged to be, “an example of a development that achieves two seemingly opposing outcomes: to both integrate within an existing bucolic landscape, and to impose a manmade ‘statement’ in a similar manner to country-house architecture of the past.”

Similarly, successful appeal A (ref. 3223513) was considered to provide a suitable statement with the Inspector commenting, “In the true traditions of country houses, the placement of a well-designed building as proposed would provide that suitable focal-point and make sense of the landscape forms, the lakes and the valley, on the removal of the fishery use.”

Unfortunately Inspectors' opinions differ and the same approach was unsuccessful in appeal B (ref. 3280777) at River View East Bridgford where the Inspector noted, “it is not the appellant’s intention to screen the development. Indeed, the DRS recognised that the dwelling would be a striking and uncompromising approach to building in the landscape. However, in the above views, the architecturally distinctive dwelling together with the clear residential use of the site would appear incongruous within its immediate countryside setting. This would not be sensitive to the defining characteristics of the local area.”

It seems the difference between a flower and a weed is being the right species in the right place (in the eye of the beholder), rather than trying to be a camouflaged wallflower.

Development that stands out whilst fitting in

It’s a conundrum. LPAs and objectors want development that “fits in” so how do you “stand out” at the same time?

One answer is to use the argument that exceptional designs, “raise standards of design more generally” in everyday developments as per NPPF 80e. The answer goes, “It may look ordinary, but it raises the standard in such-and-such a way to inspire and be repeated in many future developments”.

For example, successful appeal D overlooking the River Severn at Fitz was considered by the Inspector, “a modern interpretation of a traditional style of English architecture that has been appropriately executed and, as such, could be an exemplar for similar development.”

Another Inspector commended appeal B’s circular dwelling as having, “the potential to raise standards of design more generally through the delivery of a programme of training and skills workshops which could be secured by condition.” Certainly providing training workshops may be worth offering, particularly as they may double as a promotional exercise. In any event, “Any well designed scheme is likely to assist in raising standards of design by setting an example that others should follow” as noted by the Inspector in appeal C at Summer Hill. It is a good argument, but does not guarantee success.

Another answer to the conundrum is to apply a humorous twist or a good story to make the design stand out. Successful appeal F (the Water Lily floating house, ref 3291091) clearly captured the Inspector’s imagination noting it, “would communicate the form of a water lily with the pedestrian bridge being the stalk. In this respect, it would have a unique, whimsical, and attractive architectural appearance and sculptural quality of a high order. The proposal would not be especially large, bold, or assertive, but architecture need not be so to be of a high standard.”

The Inspector was very taken by the railway carriages concept in appeal A at Yew Tree Farm and the story of the former railway being reflected in the architectural design of the main house. The history of the site reflected in the design captured the Inspector's imagination and helped win the appeal.

A strong story ‘stands out’ even when building elements are toned down. As they say, "Every great design begins with an even better story.”

Hidden design elements in a development

One consolation to architects is the credit given to design elements that cannot be seen by the public. For example, in appeal B the Inspector noted, “internal spaces can be important in considering the quality of the architecture”.

Successful appeal F involved the Water Lily house using experimental engineering to create a floating foundation. The Inspector was impressed noting, “An assessment of architectural quality can go beyond the appearance of the building and include other matters such as the construction method.” Clearly design does not need to be external to 'count' in an appeal.

Landscape mitigation is not enhancement

Inspectors were brutal in discounting tree planting and sensitive landscaping around the proposed dwelling, typically treating it as mitigation that doesn't count as a positive benefit.

For example, appeal E at Myddle included solar panels set into hidden ha-ha’s sunk into the ground and screened from wider views. This creative means of integrating the development into the landscape did not impress the Inspector, who considered it merely mitigation rather than enhancement.

Using a Design Review Service

A number of the case studies impressed the Inspector by demonstrating that the design had been informed by the advice of an independent design review service (DRS). NPPF paragraph 133 recommends the use of such tools, albeit from a LPA’s perspective. Applicants may engage their regional Design Review Panel to provide feedback on their designs, if they dare.

The use of a design review process was certainly a factor in the success of appeal D overlooking the River Severn at Fitz where the Inspector noted,

“The proposal has had a protracted design process. Elements such as a central dome have been altered or eliminated and through a process of consultation and evolution …...The design process has been subject to robust review….I appreciate that appearance and design can be a subjective matter but consider that in this case, the rigorous design process has resulted in a proposal that successfully blends traditional and modern styles.”

A Design Review Service (DRS) was also employed in unsuccessful appeals B, C & E, where all the appeal Decisions noted the use of a DRS and agreed the proposals were well designed. Unfortunately the designs were considered not sufficiently outstanding or exceptional for the purposes of meeting NPPF 80e, but nevertheless gained significant design credibility from the design review process.

A danger of design review is that changes to one element lead to a discontinuity in the overall design, as occurred in appeal E at Myddle where the Inspector felt the window shapes and proportions, amended by the design review process, did not follow the visual lines of the wider building. A design review service is unfortunately not a golden ticket to success.

Use of CGI in planning appeals

An interesting warning is presented by appeal B, the circular development at River View, East Bridgford. The appellant sought to submit a Computer Generated Image (CGI) fly-through video of the proposal as part of a written reps appeal. The Inspector refused to accept the CGI as evidence on the basis that members of the public may not have suitable facilities to view the CGI.

Those who seek to bolster their design evidence in an appeal should take note and play safe by including additional images within their Appeal Statement of Case.

Interaction between NPPF 80e and Local Plan policies

The various iterations in the NPPF over the years means older Local Plan policies for exceptional development in the countryside may be inconsistent with policy 80(e) and therefore “out of date” as per NPPF paragraph 11(d). It is also worth noting NPPF 80e allows bigger dwellings than Local Plan “replacement” dwellings in Green Belt areas.

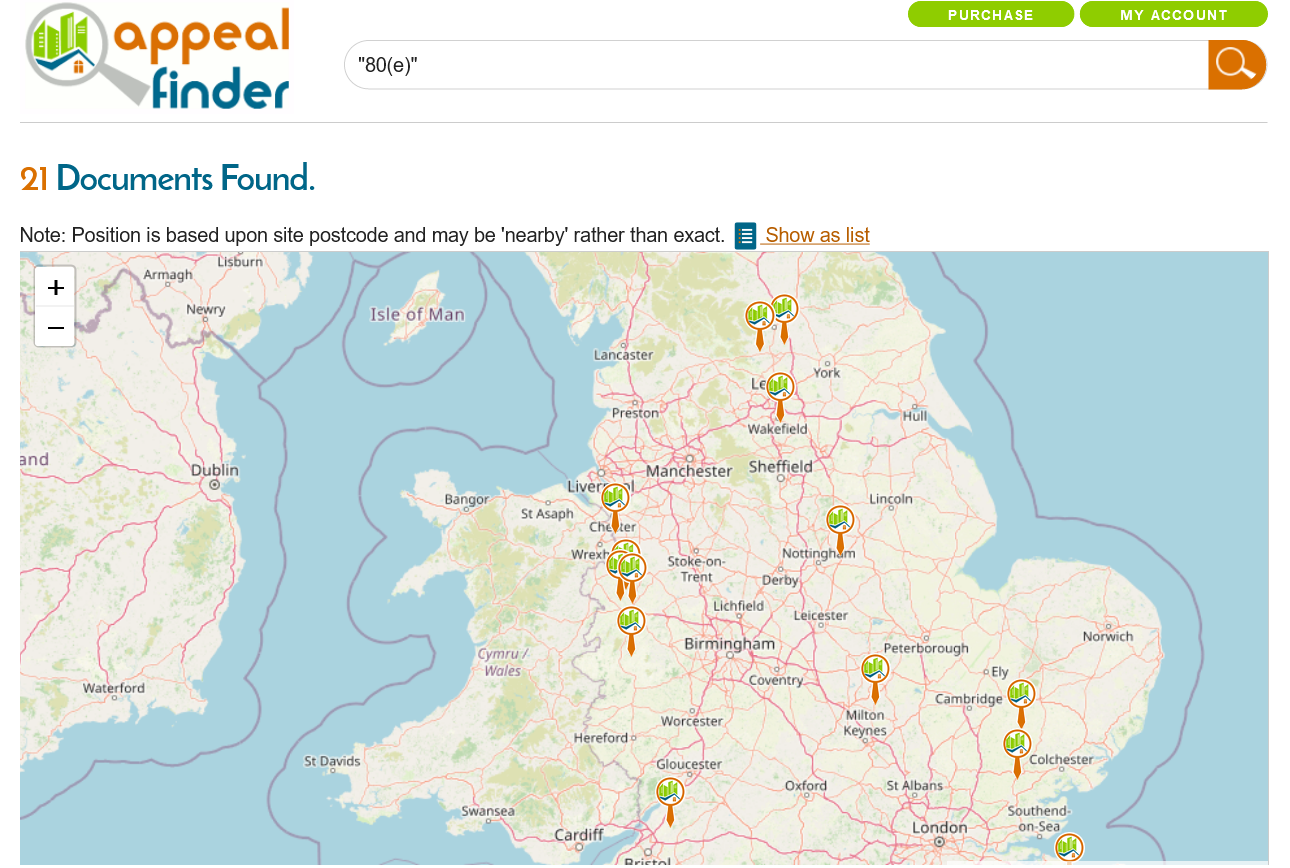

Identifying appeals featuring interesting designs

Design ideas abound in section 80e appeals, offering inspiration for more run-of-the-mill developments. To find such appeals on Appeal Finder simply put “80(e)” in the keyword search (always use inverted commas around the keyword) as shown in the screenshot below. “79(e)” finds a further 52 appeals that predate the 2021 NPPF – plenty of bedtime reading for the very keen.

If you aren’t already a subscriber, it’s easy to sign up for a free month’s trial. Just go to the bottom of our Home page and click on ‘Free Trial Request’ and we’ll send you temporary log-in details.