One way to be successful at barn conversion and Class Q applications

Are you facing a difficult class Q or barn conversion application? Don’t despair; you can take heart from many successful appeals. Looking at others’ experiences is also a great way of picking up hints and tips that can make all the difference in gaining consent.

Grab a cup of coffee and enjoy the whistle-stop tour of half a dozen interesting cases to give you a fresh perspective on:

• when is a new build not a rebuild;

• the amazing case of success in flood zone 3;

• access and design issues to be aware of;

• dealing with noise & contamination objections;

• spillover battles, like flues and garden enlargement;

• discussing strategy with your client and one surefire way to be more successful.

Don’t you just love-hate borderline cases? The ones where the client is enthusiastic and you are sucking in your teeth…. When it looks impossible, don’t forget every year many barns get planning consent to be turned into dwellings despite all obstacles. The photo below is one which I really thought I’d lose, and was dumbstuck when Warrington Borough Council gave prior approval for class Q conversion to five dwellings. Never despair!

When does a Class Q conversion get classed as a re-build?

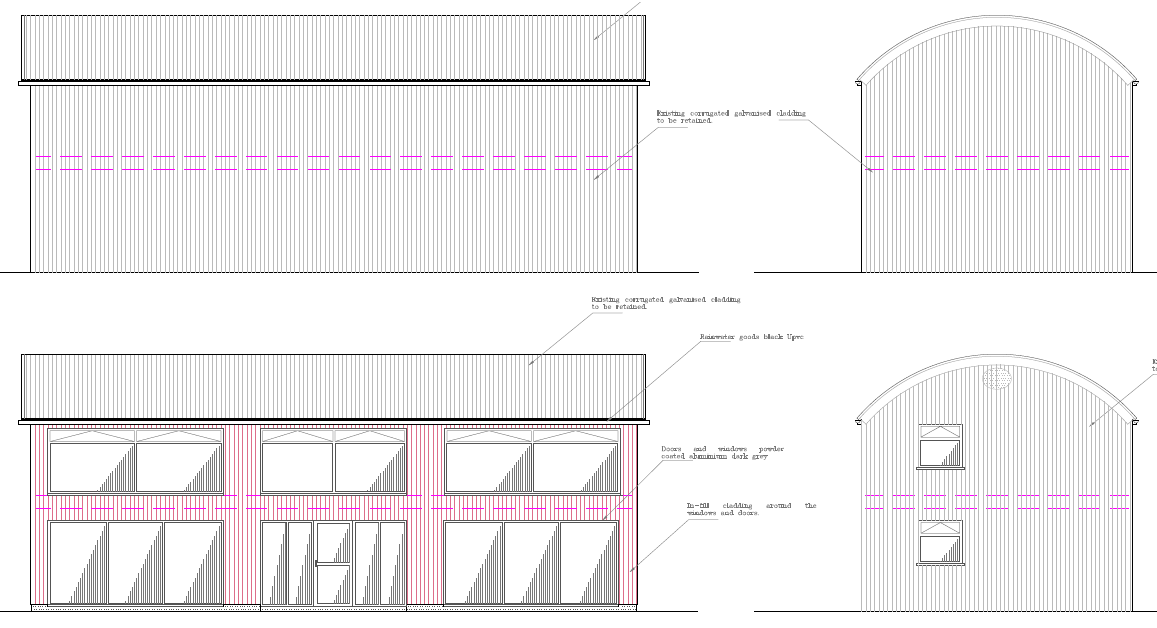

The main issue in the appeal for the barn pictured below was whether it qualified as a “conversion”. The proposal was to retain the existing steel frame and 74% of the existing corrugated metal cladding and roof. A new fully insulated timber frame with walls and glazing was to be created inside the barn, like a nest of two Russian Dolls, with one effectively within the other.

The Council’s case was the proposed works went beyond a conversion. In dealing with this issue, the Inspector quoted the guidelines in the Planning Practice Guidance which in turn is based on the case law of Hibbitt v SSCLG. Crucially, creating a new dwelling within the existing barn and which does not significantly alter the existing outer envelope does not amount to a re-building of pre-existing structures.

The planning Inspector in this case found that the “proposed development would comply with paragraph Q.1(i) of the GPDO in terms of the extent or scale of building operations being reasonably necessary to convert the building with respect to Class Q(b)” (appeal no. 3299860).

There are many similar examples of appeals allowed for what are effectively new dwellings sited inside an existing barn, shielded by the roof of the existing barn. It takes the concept of “reduce, re-use, recycle” to a whole new level.

Successful planning appeal for Class Q consent in Flood Zone 3

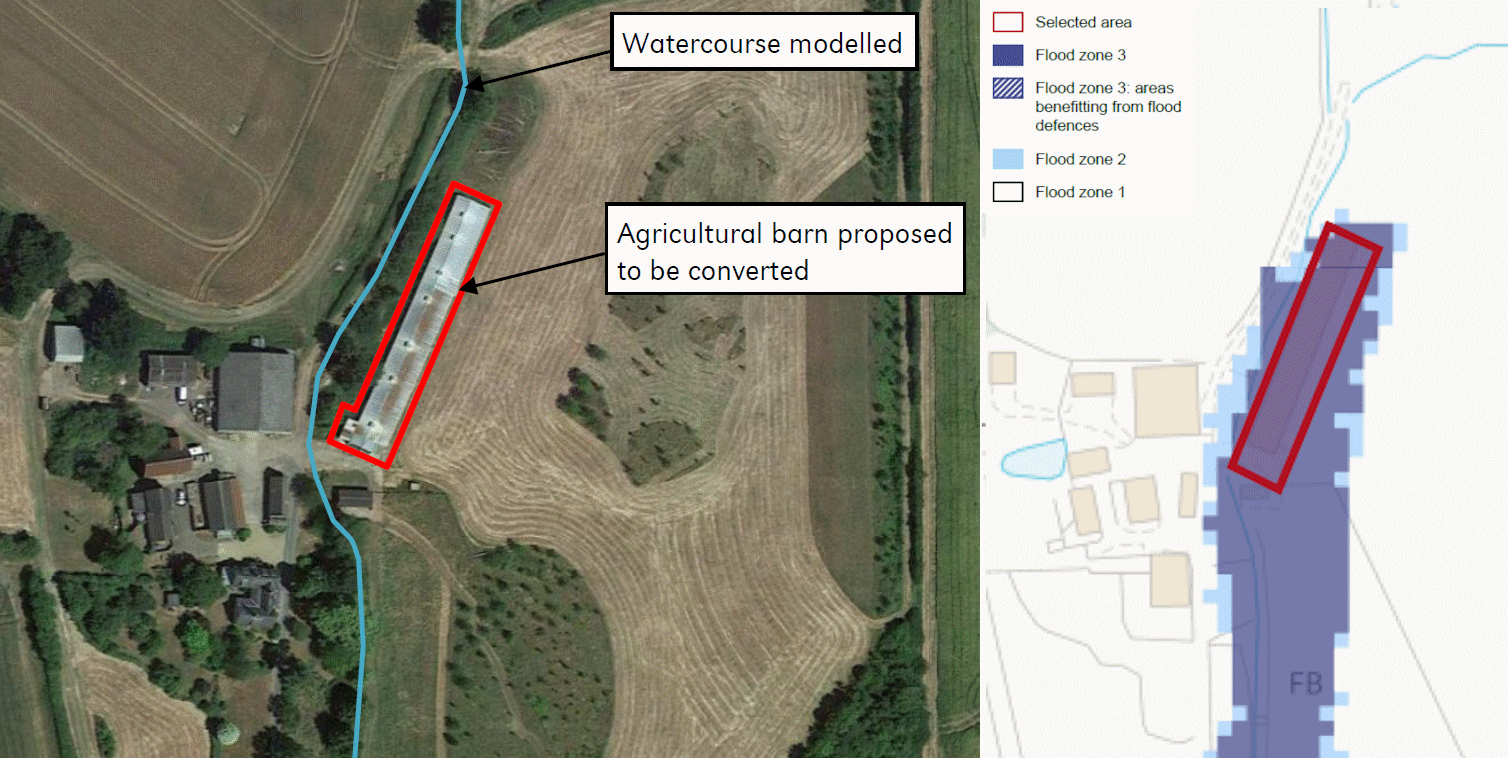

This allowed appeal is a fascinating case for a number of reasons. Firstly, after reading the detailed Flood Risk Assessment (FRA), the Environment Agency offered no objection despite the barn being located in Flood Zone 3.

The FRA made a hydaulic model of the stream and identified the height of flooding in a 1 in 1000 year flood plus 25% allowance for climate change. The applicant dealt with this by proposing a finished floor level 17cm higher. The applicant also had an Emergency Flood Plan to address safe means of escape in the event of flooding. This resulted in the Environment Agency having no objection to the class Q application.

Not to be defeated, the Council countered that the proposed raised floor might not be supported by the existing foundations of the barn. In the subsequent appeal, the planning Inspector impressively batted this argument aside, noting National Planning Practice Guidance (NPPG) states that for the building to function as a dwelling it may be appropriate to undertake internal structural works, including a raised floor or a mezzanine floor (Paragraph: 105 Reference ID: 13-105-20180615). Interestingly the Inspector went on to comment the NPPG places no distinction or restriction on whether these works are structural, or not, provided that they are reasonably necessary.

The third reason this appeal is fascinating is procedural – bear with me, because this actually raises some quite interesting points.

The Council missed the 56-day deadline to determine a class Q application. It then refused to issue a certificate of lawful use or development (LDC), claiming the works to raise the floor went beyond what was permitted by class Q. With the two issues so intertwined you go round forever in a circular argument. To cut the circle, the appeal Inspector expressed the main issue as, “whether the Council’s decision to refuse to issue a LDC for the application was well-founded.”

Interestingly, the Inspector noted, “In this type of appeal (ie. a LDC), the onus of proof lies with the appellant, with the relevant test on the balance of probabilities. For the avoidance of doubt, the appellant’s evidence does not need to be corroborated with independent evidence in order to be accepted. If the Council has no evidence of its own, or from others, to make the appellant’s version of events less than probable, there is no good reason to dismiss the appeal, provided the appellant’s evidence is sufficiently precise and unambiguous.”

As the Council had not made any timely objections on any grounds (including flooding), the Class Q was deemed to have been granted. The only question was whether it qualified for class Q conversion in the first place. The Inspector allowed the appeal because, “on the basis of the evidence before me and balance of probability, the existing building is suitable for conversion to a residential use and the identified building operations would not go beyond what are reasonably necessary to facilitate the building to function as a dwelling.” (appeal ref 3301666).

Next time you have a site you despair of getting consent, remember persistence and common sense do sometimes win the day.

Tripped up by access issues

Far be it from me to suggest it’s always plain sailing. In fact I think we learn more from dismissed appeals, as it shows the pitfalls to be avoided.

The case pictured below is located on the bleak Pennines above Rawtenstall near a public footpath. It’s sited beside an existing farmhouse on a single track access road approximately 2.25km long (appeal ref. 3260238). This case illustrates the danger of “forward visibility” issues on single track access roads. One of the two reasons the Inspector dismissed the appeal were adverse highways and traffic impacts because, “whilst at points forward visibility along the road is good, in other places it is much more limited.”

Even at slow speeds, blind bends and blind summits on a narrow access road present a real problem as they generally won’t meet the required stopping sight distances (SSD). National guidelines in ‘Manual for Streets’ is geared to urban areas but it nevertheless sets expectations for the highways authority. It’s best to warn applicants early on that they may need to widen parts of the access road if there are highway objections, particularly where there’s more than one dwelling proposed. Unfortunately this may make some proposals unviable.

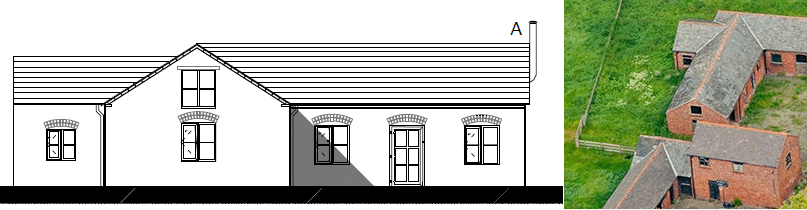

Design issues and subjectivity in planning decisions

The class Q proposals in the Rawtenstall case were for rendering the lower parts of the blockwork walls and cladding the upper part in timber, to create four modest dwellings. Meeting the “design or external appearance” requirement is notoriously subjective and in this case the Inspector noted, “the proposal would introduce a number of windows and doors on all elevations….their domestic character would sit uncomfortably with the agricultural form of the building which would be to the visual detriment of both the building and the surrounding area.” She dismissed the appeal as failing to comply with both highways and external appearance requirements.

Personally I find the above barn ugly and struggle to understand how render, timber cladding and some new windows add up to visual detriment, but the point is, design and appearance is highly subjective and some you’ll win, and others you won’t. I guess the key is to not take it personally.

Class Q noise and contamination issues

Back to positive news with the example appeal below being allowed with an award of costs against the Council (ref. 3290693). Two class Q dwellings were proposed on the site below. Neighbours claimed this would give rise to unacceptable noise from vehicles on the part-gravel access track which curves around the back of their homes.

The statutory consultee raised no objection in relation to noise but nevertheless the Council included noise as a reason for refusal. To address this the applicant paid for a noise survey and submitted it with their appeal. This provided technical evidence that even the maximum number of cars wouldn’t create unacceptable noise. Meanwhile the Council failed to provide any professional technical evidence to to support this reason for their refusal of the class Q application. The Inspector took a dim view of this behaviour and awarded costs against the Council, ordering them to pay the appellant the cost of the Noise Survey.

If you are faced with a similar “make weight” reason for refusal, it certainly is safest to address it with professional evidence but it is also well worth accompanying the appeal with an application for costs.

This appeal (ref. 3290693) also highlights the straightforward nature of most contamination concerns. The Council’s statutory consultee recommended conditions to deal with contamination, namely a Site Investigation report followed, if necessary, by a Remediation Method Statement. The LPA tried to argue contamination is only properly dealt with by a planning application rather than through the prior approval process. The Inspector’s Costs Decision gives this argument short shrift, concluding the Council acted unreasonably as conditions are perfectly capable of dealing with most contamination issues.

No doubt for the benefit of the neighbours, the Inspector’s Decision Notice explicitly noted, “Concerns such as the impact on views of the countryside, privacy and overlooking, wildlife and livestock and security during construction do not fall within those matters that can be considered under Class Q.” Quite so.

Sour grapes after the barn conversion has commenced

When you celebrate getting prior approval, be careful! There are spillover battles in which a determined case officer can make life difficult for everyone.

As a cautionary tale, I once obtained Class Q consent because the Council missed the 56-day deadline. A few years later they claimed the consent was null-and-void because, to meet building regulations, the flue from the boiler poked beyond the envelope of the original agricultural building as shown in the drawing below. This flue would be very unlikely to be spotted by any casual passer-by except a resolutely determined officer. My client was in a bullish mood and inclined to wait for an enforcement notice, then appeal, but in the end it was resolved with a standard planning application for consent for a flue. I’m not sure if it made the officer feel better or not.

My client was in a bullish mood and inclined to wait for an enforcement notice, then appeal, but in the end it was resolved with a standard planning application for consent for a flue. I’m not sure if it made the officer feel better or not.

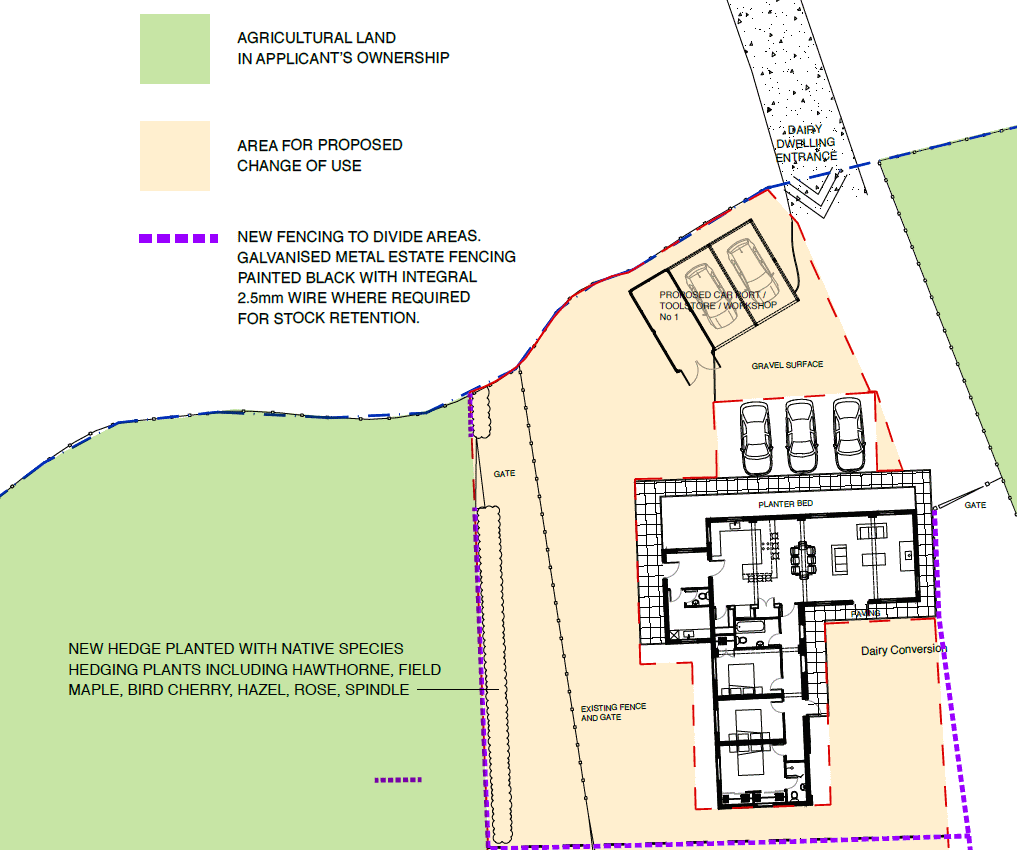

A few years after the conversion we submitted an application to enlarge the garden and add a car port. This was refused by the Council but later won on appeal, after we demonstrated that all the neighbouring half-dozen homes had similar sized gardens. The Inspector seemed to think the officer was just a little too pedantic about class Q and had lost sight of the reality of this being someone’s home, on a lane with many other houses. Sometimes a dose of common sense still works in tipping an appeal decision.

Strategy and essential discussions with clients before you start

I love the phrase, “Fools barge in where angels fear to tread.” In this case, the angel is the planner who realises the problems you’re going to face while your client is, well let’s say optimistic and unaware of the challenges ahead. So after you’ve sucked in your teeth, how do you proceed without bursting their balloon?

It’s worth mentioning to clients at the outset the various issues that might arise. In doing this, it helps to have some positive and negative examples up your sleeve of appeals which have been successful and others which failed. Talking about other cases can allow discussion of the issues from a more dispassionate perspective, as the client is not personally attached to those schemes.

When searching Appeal Finder for useful examples remember to put “Class Q” in inverted commas, otherwise the search will throw up some Class E applications with drawing Q….

A friend once gave me advice on separating objectives (eg. getting planning permission or prior approval) from the underlying aim (eg. finding somewhere for Jimmy to live, or finding a viable new use for an unwanted barn). It’s important to be clear that winning planning consent is just a single objective, merely one stepping stone on a route to achieve the overarching aim. There may be other ways to get there, via alternative paths using different objectives. Planning consent is only a stepping stone to an end. It’s not everything. This perspective helps enormously in keeping you sane.

One way to be more successful in gaining Class Q prior approval or planning consent

In the army they think through their adversary’s perspective in order to anticipate how best to engage. Likewise it’s well worth trying to understand your opponent’s mindset before you enter the battlefield. The best way I have found to do this is to quickly read through some appeal Decision Notices. It’s also possible to do this with planning officers’ reports, but they are usually not as short and succinct as an appeal decision.

A quick 5 – 10 minute read of others’ appeals gets you into the decision-makers’ frame of mind and presents both the applicant’s and objectors’ points-of-view. This is very useful preparation for battle and allows you to avoid the worst of the landmines. Reading a few appeal Decision Notices is a great way of making your own planning case more watertight, as discussed in my February blog on what you can learn from planning appeals to improve your own chances of success.

To find appeals which act as your critical friend, helping you to predict the likely shape of the battlefield ahead, use the search on our Home page. Armed with these, you’ll find it quicker and easier to make your own planning case. Good luck!